A DOLL’S HOUSE REHEARSAL PROCESS: SUMMING UP – DIRECTOR JAKE MURRAY 25.9.2022

So what have we learnt? Firstly, Ibsen’s characterisation, even at this early stage of his period of writing naturalistic plays, was far more multifarious than we could have imagined. All the characters in the play are rich to explore, even the Nurse, whose one scene with Nora contains a wealth of moving detail in two short pages. A Doll’s House is often seen as being all about Nora, and Nora is undoubtedly the centre of it and the role that drives the material, but Ibsen rounds off every one of his characters, keeping you guessing about them at every stage. All of them have backstories, hidden depths and, most of all, a wounded vulnerability that makes them all sympathetic at key moments. Even Torvald has his humanity, as his broken state at the end of the play shows. You realise that Ibsen’s world is one in which the apparent comfort of the bourgeois household conceals depths and tensions no-one can escape. Society’s laws hold everyone together, but not without a cost. Nora’s self-sacrifice as a wife almost destroys her; Christine’s similar self-sacrifice before the play begins has almost done the same; Rank’s self-effacing charm and urbane nature hides loneliness and self-loathing; the crushing judgement of society turns Krogstad into a monster and even Torvald’s privilege and entitlement prove brittle and weak when faced with the shock of losing his wife.

All of this makes acting these roles a vulnerable and challenging experience. Actors must play the emotional turmoil underneath the social mask, none more so than the actress playing Nora. The strain of trying to navigate the pressure of the first two acts nearly destroys her. We see the way in which she is forced into a false relationship with everyone, including her friend Christine, almost breaks her. Her resourcefulness in trying to save her marriage proves her to be a truly remarkable woman, but ultimately its her ability to see the truth and allow herself to be transformed that makes her the heroine she is. Nora’s self-realisation at the end is the ultimate prize of the play. Charting this inner journey is a huge challenge for an actress, who is effectively acting non-stop for 90% of the play, never leaving the stage until the beginning of the final act which becomes about Krogstad and Christine. Its an assault course, but also a triumph for any actress worth her salt. Ours, Hannah Ellis Ryan, has risen to the challenge with her whole being.

Other things we’ve discovered: the evasiveness of Ibsen’s characters. Honesty, direct conversation in which people talk about the feelings without disguise, only occurs in the final act. No-one understood the way we wear masks in society better than Ibsen. Acts 1 and 2 are public acts, all going in under the gaze of society, Act 3 happens behind closed doors. Its only here were Torvald and Nora remove their masks and show who they really are, as do Christine and Krogstad. The intimacy of the writing in this Act foreshadows Ibsen’s later plays, all of which revolve around this same directness. Before then all the characters of A Doll’s House hide their feelings and speak in codes, they hold back truths and keep secrets. Navigating this as actors and director is also a huge challenge. Most of the plays Elysium has done hitherto have been very direct emotionally – Strindberg, Fugard, Giurgis – people say what they mean and mean what they say. In Ibsen its not so simple. Working out when something is meant to be taken literally or when it is to be taken as ambiguous is a huge challenge. For instance, in Act 1 Nora tells Christine that Torvald once got ‘almost angry’ with her. Does she mean that, or does she mean he got very angry but cannot admit it to herself or Christine? This is what makes Ibsen a great playwright, but also a difficult, albeit exhilarating one to play.

We’ve also discovered what a sensual writer Ibsen was. Sexuality is not something normally associated with his plays, but in fact it is always present, seething beneath the apparently genteel veneer of the characters’ behaviour. The scene in Act 2 in which Nora shows Rank her stockings, or in Act 3 in which Torvald tries to seduce Nora show how Ibsen understood sexuality and its complex issues of manipulation and consent. These things are often missed completely in production, and so a whole dimension of the writing is lost. Once again, he seems incredibly ahead of his time.

Lastly, an interesting element to the play which is not often talked about is how it uses but subverts and rejects the devices of melodrama. Its easy to miss today as melodrama no longer exists as a stage form for us, but in Ibsen’s day it was the dominant genre of the stage. In A Doll’s House Ibsen takes all sorts of elements of it – blackmail, a fatal letter, a husband who promises to stand by his wife and protect her against scandal, a heroic wife willing to sacrifice herself by throwing herself into a lake to protect her husband from shame – only to completely shatter them in the last act. When Torvald tells Nora to ‘stop being theatrical’ or ‘melodramatic’ when she tells him she’s loved more than anything in her life or that when she is gone from this world he will be free, Ibsen is tearing up the sentimental tropes of melodrama. The husband is not heroic, the wife does not sacrifice herself, rather the husband and cowardly, selfish and weak and the wife walks out on him, newly strong inside. Ibsen was working with his audiences’ expectations, hooking them into the story, tricking them into thinking they know where it is going only to completely explode it all in the final act.

Is it too presumptuous to say that Ibsen loathed melodrama and, in his desire to modernise theatre deliberately constructed a play that parodied and exposed it? Or that he did it most effectively by reversing the stock ending and investing the story with a moral and psychological depth that forced people into emotional territories they had not expected to go to?

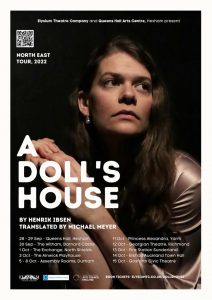

A Doll’s House is the most epic and ambitious play we at Elysium have yet done. Its a beast of a play, a real mountain to climb, but as we approach our opening night on Wednesday at Queen’s Hall Arts Centre we hope our work will pay off, and the audiences will be as bowled over by the power of Ibsen’s writing as we have.

——————————————————————————————————

UNSEEN PODCAST by BRIDIE JACKSON – DIRECTOR JAKE MURRAY DISCUSSES A DOLL’S HOUSE 14.9.2022

Bridie Jackson is a North Eastern singer, songwriter, musician and composer. She also hosts the Unseen Podcasts, which covers the Arts in Northumberland and Queen’s Hall Arts Centre, Hexham.

Here she discusses ‘A Doll’s House’ with Elysium TC artistic director Jake Murray, as well as other goings on at Queen’s Hall:

https://unseenqh.podbean.com/e/unseen-episode-6-what-s-next/

——————————————————————————————————–

A DOLL’S HOUSE – Q&A WITH WYNNE POTTS – PLAYING ANNE-MARIE 13.9.2022

Day two of our second week & it feels like everything we thought we knew about the play we don’t. Its a much more dynamic, mould-busting play than we thought. The thriller aspect – will Nora survive Krogstad’s blackmail and save her marriage – works powerfully, but also as a means for Ibsen to put his heroine under pressure so her defences crack open and we see the remarkable woman underneath. He pushes her to extremes, almost to the edge of mental breakdown – quite faring for a play written in the 1870s – but does so not to torture here but reveal her humanity. In the end its only when everything is stripped away, when she can no longer hide, does the catastrophe come which blows her open and turns her into the woman she is at the end. As Hannah, our Nora, put it, she must ‘break down or break through’.

We looked at several scenes today: Christine’s two scenes with Nora in Act 2, Torvald’s last scene in Act 1 & first scene in Act 2 and Rank’s Act 2 scene with Nora. Reaching the scene in which Nora panics and is helped by Christine helped us get a handle on Mrs Linde. Because he writes such rounded characters, you can’t play the opening scenes of any of his plays unless you understand the characters in their totality. In the same way that looking at later scenes helped us with Krogstad and Torvald, so did looking at what Christine would become. Immediately we understood that who she ends the play as must be implicit in the beginning. In this way we hope to add depth to her first, very tricky expositional scene with Nora.

Torvald’s scenes continued to reveal the contradictions in his character: the narcissism, the self-flattery, the controlling, infantalising behaviour towards Nora, but also the moments in which he appears to her to be the ideal husband (to borrow Wilde’s phrase). Nora has to believe that Torvald will stand by her if there is a crisis, otherwise the final scene won’t work. Ibsen places a huge challenge on the actor playing Torvald in the preceding scenes so were kept guessing as to who or what he really is. Danny Solomon is doing a great job of showing how he can slip from tendentious, morally superior moral baby to sincere, loving husband in just a few lines.

Most interesting, however, was the extraordinary scene in which Nora tries to ‘seduce’ Dr Rank (I use the word advisedly, as she isn’t really trying to seduce him, just get him to help her). The scene is highly sexual and suggestive, and we were mindful that in Ibsen’s day would be highly erotic, so demands of actors real bravery not only in terms of how they present that sexuality, but also how honest they are willing to be about the painful emotional negotiations going on in the scene. Again, Ibsen’s ability to be so ahead of his time in which he saw people came to the floor. Its an astonishing scene, and we think will surprise people.

And now we come to the last of our Q&As with the actors in the play. This one is with Wynne Potts, the actress playing Anne-Marie (an amalgamation of Helen and Anne-Marie in the original):

Tell us a little about your work as an actor so far:

I trained as an actor, as a mature student, at The Royal Central School of Speech & Drama & Rose Bruford College of Theatre & Performance (combining 2 part time courses.) My acting experience so far has involved straight & musical theatre, in traditional theatre venues, such as The Crucible Theatre, Sheffield, & also in less conventional spaces such as stately homes, churches & in art galleries – as a Storyteller, for example, with ‘The Border Readers’. I’ve acted in short & independent films, for TV, such as comedy sketches for BBC1, written by Horrible Histories writer, Terry Deary, & a commercial for ITV, plus Web series for award-winning Wolfpack Productions. I have just completed a run in a children’s Musical Theatre play at Alphabetti Theatre, in which I played 5 roles, involving singing, guitar & puppetry.

Is this the first time you have worked with Elysium?:

I was part of the Servants’ Ensemble in their production of Miss Julie which played at Queen’s Hall Arts Centre in Hexham back in 2019. But

What character are you playing?:

I’m playing Anne Marie, who is the Maid & Nanny.

How do you see the character? What are your initial impressions from reading the script?:

My initial impression of the character is of a woman who’s diligent at her job, trustworthy, kind, compassionate. She is committed to caring for the children +Nora + the family as a whole, partly as its in her nature, & also becos this family/household has been her source of security all these (25+) years that she’s been in their employment. Their security is her security. I also think she carries alot of subconscious pain about having had to give up her child, but that it’s stuffed right down: she’s not conscious of it most of the time. But it surfaces when she has that conversation with Nora on pg 55 – especially when she refers to having heard from her daughter twice (only twice in her life!) once being when she got married.

How do you prepare for a role before rehearsals begin? What preparation have you done for Anne-Marie?:

I read the scenes I’m going to be in several times, first of all allowing my instincts to ‘feel’ a sense of the action, & the character. Then I think about it more logically, identifying what my character’s superobjective might be, & her objectives for each scene, & then decide on ‘actions’ by which my character attempts to achieve her objectives. But I ‘hold those actions loosely’ as I want to be flexible & responsive to the Director’s vision +to how the other actors in the scene play things in rehearsal +how it flows +emerges as we explore. I’ve done the above for Anne Marie, & feel her superobjective is perhaps ‘to protect’ +to care for people’s needs, both practically + in terms of their emotional well being. She’d want to protect the peace of the family. So she would seek to use actions like ‘to encourage,’ even, altho she’s ‘staff’, ‘to befriend’, since there is a certain closeness + familiarity between myself & Nora, owing to the fact that I was Nora’s nurse maid, so I more or less brought her up from childhood, almost taking a ‘Mother’ role in her life. That former position gives me the confidence to, occasionally, respectfully, attempt ‘to guide’ Nora. & often, i’ve found the need to use actions like ‘to prepare’, ‘/to alert’, as things are happening (secret visiting cards, letters) which I feel the need to pre-warn Nora of, always from a perspective of wanting to protect & keep the peace of this family.

What do you think are the main challenges with your character as an actor?

I’m a visual person, a lover of Nature, +I was inspired years ago by how Anthony Sher, in his book ‘The Year of the King’, described how the landscape played a part in his creation of his character. Ive enjoyed absorbing old photographs of Norway in the 19th Century, to feel the atmosphere, +feed my imagination. Through such photos, I noticed how close to water Norweigans were/are, which our Director Jake confirmed. Since I’m writing part of this answer after our Jake gave us his introduction on Day 1 of rehearsals, i’ll add that he explained how much a part religion played in Norweigan life in the 19th Century, & that it was predominantly Lutheranism, or Lutheran Pietism, quite a different form of Christianity to the Anglicanism most English people are used to in our day. I’ve read more on this since that Introduction, & feel that my character’s motivation to want to be of help & to protect +care for her employers, Nora in particular, could have been drawn +motivated, in part, by her faith: the notion of serving one’s fellow man, concern for the neighbour in need.

Is this the first time you have worked on an Ibsen?

I have worked on Ibsen plays before. In fact I’ve played a different role in an excerpt from this very play, at Drama School – I played Christine Linde. I’ve also played Mrs Elvsted in an extract from Hedda Gabler, in a performance as part of a training course at The Crucible, Sheffield.

What do you think are the main challenges of working on an Ibsen? How is he different/ the same to other playwrights?

One of the challenges of Ibsen, which happens to be one of the things I love most of all about a period piece, is researching & getting an imaginative sense of the historical era in which it is set. As someone who loves history, I am excited about imaginatively ‘immersing’ myself in the epoch in history in which Ibsen was writing this piece, its mores & conventions, so as to understand the full significance of the characters’ actions and words, which may be quite different, when seen from the perspective of the world view of that time. Communicating the play’s full meaning, in all its various facets, to a modern audience could be a challenge, but not an insurmountable one. & if any company can achieve it, I believe Elysium can.

But, in our initial read through, towards the end of the play, I was quite amazed at how ‘modern’ the ideas were that were being expressed – such as the notion of wanting ‘to find out the truth about myself & about life’, ‘& try to find my own answer’ & ‘to find out whether (established religion) was right – ot anyway, whether its right for me.’ Such lines could easily feature in a contemporary coming- of- age drama.

What do you hope the audience will take away from the production?

What I hope the audience will take away from the production is the realisation that people of a different era (& geographical location) weren’t all that different to us in our day. Human beings feel & suffer & strive & hope, no matter when in the timeline of history one has lived. I hope they have a sense of real compassion for, & empathy with, the characters in the play, realising that they have all been hemmed in & indoctrinated to a certain degree by the expectations & demands upon them of man-made institutions + rules of society. & to be inspired by the courage of all the characters who’ve dared to take a chance (what in Ibsen’s day were far more risky steps to take) & make a significant change, to reach out for something more in life. Cos, altho Nora takes the biggest step of all, she isn’t the only character to do so: Christine & Krogstad each take a risk in trying for love a second time, late in life. Even Torvald is willing to try to change, albeit TOO late.

I also hope the audience come away feeling a sense of gratitude for the incredible freedoms we have in our 21st century lives, where one can openly embrace a seemingly infinite range of self expression, philosophy, & lifestyle. & yet do we see ourselves as, or even feel, ‘free’?

A DOLL’S HOUSE – Q&A WITH MICHAEL BLAIR – PLAYING KROGSTAD – 12.9.2022

So we begin our second week of rehearsals. The first week ended with a dance call for Hannah in preparation for the Tarantella scene in Act 2, completing the first Christine Linde scene and then looking at Krogstad. Its always a huge challenge working through the opening section of a play because you don’t yet know the arc of the drama or who the characters are. In A Doll’s House this is exacerbated by the enormous amounts of exposition in the text. Ibsen was pioneering naturalistic drama and would hone his skills in this field as he went on. A Doll’s House‘s opening scenes present a considerable challenge, however, as he hadn’t yet perfected what he was doing. Everyone did sterling work, but we all went home on the weekend feeling both exhilarated and excited, but also very aware of the mountain we had to climb, and how daunting the play was. Ibsen is a playwright in a league of his own. If you can do Ibsen your can do anything. But… its not easy! One of the reasons is the way his characters hide what they say. Most Elysium productions have been very extrovert and direct; characters say what they feel and are not afraid to argue or fight. Ibsen’s characters wear masks and hide their motivations, sometimes because they don’t know them themselves. We have already started to find that every line has about 50 layers of meaning to it. How you convey that is a real challenge.

So as this week began we decided to start to work out of sequence and get to the dramatic core of each character. We discussed Torvald and Nora and laid the ground for the second scene in Act One in which Torvald’s controlling, slightly creepy behaviour starts to manifest itself. When we got to it we noticed how subtly Ibsen plays with our responses: Torvald moves effortlessly between saying the most terrifying and belittling lines to Nora, to suddenly saying deeply soulful and loving things. We realised how complex and confusing this was for Nora, who could was lost in trying to process what we was saying or doing. We were convinced this was deliberate on Ibsen’s part: he wants us to see how Nora slowly wakes up to how he treats her. Each scene reveals his narcissism and domineering nature more and more, until it becomes inescapable – or rather Nora realises she has to escape it! The way Ibsen has this scene follow Krogstad’s first scene with Nora demonstrates his effortless stagecraft. We have seen Nora threatened and bullied, but instead of being a Knight in Shining Armour Torvald reveals himself to be insensitive and morally blind. But then he knows nothing of what is going on, or the sacrifices Nora has made for him over the last seven years (seven years!). Ibsen uses layers of dramatic irony to sow confusion.

Krogstad’s scene posed lots of similarly interesting challenges. The clashes between him and Nora are superbly presented, as Ibsen shows how the balance of power between them constantly shifts. Krogstad may have gender privilege as he is a man, but Nora has class privilege because of her higher social status and her powerful husband. Like Jean and Miss Julie, both are oppressed and are oppressing in different ways. This makes their sparring doubly powerful as our sympathies shift. We also saw how by this time we have seen several sides to Nora. The woman who stands up to Krogstad appears to be a different woman who submits herself to Torvald. Its the split between these two Noras that eventually causes the dynamite of the end of the play to go off…

One interesting challenge we have become aware of is just how much society has changed, not just since the play was written but within the last few decades. The men and women in A Doll’s House all feel that marriage, parenthood, home and family are important, but these are things that mean less and less to people in our society as all four are seen as, in some way, oppressive structures. When we tour we are going to perform in very different venues, from huge theatres like the Alnwick Playhouse and the Fire Station in Sunderland, to the Durham University theatre the Assembly Rooms. How will we convince these wildly divergent audiences to invest in the aspirations of the characters so that tragedy becomes possible? That’s going to be very interesting, and we are looking forward to how post show Q&As will reflect that.

Speaking of Krogstad, here is Michael Blair, who is playing him, on the part:

Tell us a little about your work as an actor so far:

I was a late comer to this game, starting almost 10 years ago at the age of 31, but I’ve packed as much in as I can. I worked as part of a theatre company, The Letter Room, who came from Northern Stage’s NORTH programme, and we created new actor-musician theatre, gig theatre and musicals which we took to Edinburgh and toured nationally. I have performed extensively at Northern Stage, particularly Christmas shows where I played all manner of creatures real and mythical. I was part of the cast of Sting’s The Last Ship, which started its revival at Northern Stage before touring the UK and Ireland. I moved to London in the interval between lockdowns 1 and 2, but find myself returning up north for work regularly, including most recently a beautiful production of The Secret Garden which performed here in Hexham and around the North. I am a musician as well as actor, playing classical guitar, blues and jazz.

Is this the first time you have worked with Elysium?:

Apart from a few online workshops on some of the great playwrights, yes! I did work with Jake as a composer on on a Shakespeare project which unfortunately was cancelled due to Covid, but we did get some good tunes out of it!

What character are you playing?:

Krogstad.

How do you see the character? What are your initial impressions from reading the script?:

I see him as a good man who was forced to do some not-so-good things in order to survive, but who now finds himself unable to save himself and his family without doing even worse things. I see him as a good analogue for the way society and social conditions can crush people, leave them destitute, force them into crime and trap them in that cycle, hurting themselves and hurting others even more. I wouldn’t call him a victim, though. He’s a complicated little cookie. He knows what he’s doing; he makes bad choices and self-sabotages. He’s very human.

How do you prepare for a role before rehearsals begin? What preparation have you done for Krogstad?:

Oooft. It depends upon the role, I think! I’ve just finished a a job on a musical with a lot of actor-musicianship, playing or singing 14 songs and playing five characters, which had two weeks to rehearse before first performance. My process for that was to just learn everything as quickly as I can, and then hope the magic of character discovery happened in the performances once I’ve managed to relax about changing my costume in 15 seconds; which it mostly did!

Generally, I just want to fill myself with as much information as I can about the play/show as I can, read the script, read around the script, but keep myself free of assumptions and conclusions. I don’t make or finalise any massive character decisions before I get into the room; I just want to create a palette of possibilities, so that I’m ready to collaborate with everyone and create together, rather than wedge my own choices and truths into the show around me, or spend ages unpicking and unlearning things I’ve settled on. And ALWAYS be generous to the character you are playing. Find the good and go from there.

For Krogstad, I found myself going back to tried and tested exercises such as going through the play to work out a) what Krogstad says about himself and b) what other characters say about Krogstad. This is a play about appearances, perceptions, and assumptions amongst other things, so I found it really useful to just do simple exercises like that.

I also decided to begin reading the play by only reading the Krogstad’s scenes, so that I could experience the brutality of the way people treat him without seeing any discussion around him. I then went back and read the whole play again from the beginning. I don’t normally do that, but I wanted to make sure that my first thought wasn’t Nora or Helmer’s life, but Krogstad’s life. Krogstad is not part of their life; he comes in from the cold and goes back out there afterwards. Remembering that feels important. That sounds very arty-farty when I write it down, but it does makes sense to me.

What do you think are the main challenges with your character as an actor?

I think depicting his complexity and the huge competing emotions that are swirling inside him. He’s not a villain in the conventional sense, he’s a broken man in huge amounts of pain, who wants that pain to stop. He knows that he has to hurt others in order to do that. He hates that but on some level is so scarred and disenfranchised that he cannot help but revel in causing pain; he hates himself for his behaviour, but also enjoys the power it gives him. So allowing that to funnel through is the challenge. Plus, he appears and disappears three times, arriving in a different emotional state each time which is always a toughy as you have to trace that change outside of the text and usually in the wings before you go on!

Is this the first time you have worked on an Ibsen?

Yes!

What do you think are the main challenges of working on an Ibsen? How is he different/ the same to other playwrights?

Ibsen talks a lot. I love him, he’s a good lad, but he uses a lot of words… particularly when you consider modern playwrights are so economical with language in the main. These days information is exchanged so quickly and our everyday conversation is so fast! Ibsen’s characters talk a LOT. Getting your head around how the characters express themselves and honouring the language whilst maintaining that sense of emotional immediacy that comes from things bursting out of you (as they do in normal conversation) is a challenge for any person from 2022 who is performing a classical text. That’s why they are hard to do well. Get it wrong and they feel stuffy and slow. But get it right and they are electric.

What do you hope the audience will take away from the production?

Anger, maybe. Without wanting to be overly pessimistic, this play was written in the late 19th Century yet the same issues discussed by the play are prevalent today to lesser or even greater extents, but all are present, and we even have new problems because the old ones were never solved. So I think if it leaves people affected and maybe even angry, we’ve done our job.

Oh, and to have a nice night out. That would be good, too.

——————————————————————————————————

A DOLL’S HOUSE – Q&A WITH ROBIN KINGSLAND – PLAYING DR RANK – 8.9.2022

Day Four of rehearsals saw us get the play up on its feet. We mapped out the boundaries of the playing area and positioned the furniture. This all may sound very obvious, but after several days of reading the play and discussing it, suddenly turning it into something three-dimensional and physical was a revelation. People often forget that Ibsen’s characters have bodies, by which I mean to often productions focus only on the head, the rational processes of people, the intellectual ideas in the text, rather than viewing the characters as flesh and blood. Ibsen wrote ‘I am a passionate playwright, and my plays must be done passionately’; in fact his characters are just like us, driven by their bodily needs, their emotions and passions as much as they are ideas, in many cases more so. Something as simple as working through Nora coming onto the stage humming happily eating a macaroon revealed how Ibsen’s innate sense of stagecraft enabled him to create something inherently dramatic and instantly recognisable. We very quickly started to get results, creating the sense of a comfortable, warm home in which the Hellmers live.

We ascertained several things very quickly. For instance, the whole play is contained in that first scene between Torvald and Nora; the dialogue mirrors that in the climactic scene in which Torvald erupts on her. He mentions how like her father she is and how honesty is an ideal for him, we see how she tells ‘untruths’ to him, minor ones in this scene, but major ones once she is found out for forging her signature and so on. All the tensions and conflicts that eventually rip them apart are in that scene, but concealed under the banter of an apparently happy couple.

We also realised how sharply Class features in the play. Commentaries on A Doll’s House tend to focus on gender issues, gender equality and so on, but Class is just as important. The divisions between the Hellmers and Christine and Krogstad are very stark. Ibsen’s plays very subtly with this.

The trickiest thing about the play is finding the tone. Go too dark too soon and the play has nowhere to go; avoid going dark too much and the play appears shallow. What did seem clear is the necessity to present the marriage as an apparently happy one to begin with. This draws us in, makes us root for Nora and want the marriage to stay together, just as she does, until Torvald betrayed her and us with his rage at the end. To make this work we have to see what appears to be the ideal marriage, with Torvald the ideal husband. Yes, he lectures her and tells her off, but its light, and Ibsen makes the stage directions very tactile. Torvald kisses her, puts his arm round her, takes her hands; its very relaxed. With this play you cannot play the end at the beginning, Nora does not know she is being oppressed. Striking the right balance so that the audience are deceived that the marriage is a good one so they overlook the darker aspects is tight rope.

We also worked on Nora and Christine’s first scene. This was where Class came into things. The contrast between the two women is stark, and runs through every page. Finding the distance between them as well as the closeness was a real challenge, but an enjoyable one.

Tomorrow we work on to encompass Rank and Krogstad for the first time. Here is actor Robin Kingsland on playing Dr Rank:

Tell us a little about your work as an actor so far:

I didn’t train as an actor, but friends and I set up a company – Taking Steps – in Birmingham after we all left college in Worcester. Since then I have been lucky to be offered wonderful roles in dramas, comedies, musicals and one pantomime! I played Peter Lawford in “Rat Pack Confidential”, based on a biography of Frank Sinatra’s little gang by Shawn Levy. I also played Charley Malloy in Steven Berkoff’s acclaimed production of “On the Waterfront”, and the mammoth role of George in Edward Albee’s “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” with the wonderful Rapture Theatre, just North of the border in Scotland. Most recently, for the same company I played Salter in “A Number” a wonderfully dark, dense play by Caryl Churchill.

Is this the first time you have worked with Elysium?:

I have known Director Jake Murray for many years, and I’ve done several productions with him. During lockdown, I took part in the company’s online workshops with several of the members of the company, but this will be my first time actually in the same room with the Elysium actors. I’m thrilled.

What character are you playing?:

I’m playing Doctor Rank. He’s a friend of the family, and I could tell you more, but it would be a huge spoiler!

How do you see the character? What are your initial impressions from reading the script?

I do have thoughts and impressions of the character, honest, but – at the risk of sounding like a grand “Aaaahk-tooooah” – I’m reluctant to share that with you ahead of rehearsals. What I love about theatre – as opposed to writing (I also write a bit) is that it is so collaborative. You talk a lot in rehearsals, and Jake is an especially erudite and incisive director, so he will have lots of thoughts. What the other actors bring will also effect not just how you act but how you think of the character, and part of the excitement of rehearsals is “stumbling” onto something about your character that you hadn’t seen before. So everything I think right now could have been jettisoned and replaced by week two of rehearsals!

How do you prepare for a role before rehearsals begin? What preparation have you done for Rank?:

I try to stick to reading the play and familiarising myself with the “arc” of my character through the story, and just being on the balls of my feet and READY for the first day of rehearsals. I find it helps to concentrate first on just what it says in the script. For example, when I was in the stage version of the classic Marlon Brando film “On the Waterfront”, I avoided watching the film, because I just wanted to work with the story we had, and the way that storywas told.

What do you think are the main challenges with your character as an actor?

Come back and ask me in the last week of rehearsals!

Is this the first time you have worked on an Ibsen?

The long answer is: when Elysium did the online workshop in lockdown that I mentioned before, one of the playwrights Jake featured was Ibsen, so we read scenes from most of his best-known his plays. And a few years ago I was in a rare production of Ibsen’s one and only comedy – a political satire called “The League of Youth” it was a terrific production, with an adaptation by the amazing Andy Barrett, directed by Giles Croft, with whom I’ve worked many times before.

The much short answer is “Yes” – this will be my first time appearing in one of Ibsen’s classic plays.

What do you think are the main challenges of working on an Ibsen? How is he different/ the same to other playwrights?

That’s a real tough question. I don’t honestly feel it’s my job to worry about stuff like that – It’s my job to do the best job I can in making the audience see a real, human, feeling character. For the rest, I think you have to trust your director. And as I say, Jake is something of an authority on Ibsen, as well as being a fine director of actors, so I feel I’m in safe hands.

What would you like the audience to take away from the play?

On behalf of Front of House theatre staff everywhere, can I say – All their litter!

——————————————————————————-

A DOLL’S HOUSE – Q&A WITH HEATHER CARROLL – PLAYING CHRISTINE 7.9.2022

Day three has continued our prices of dealing deep into the characters and themes of the play. Instead of getting the show on its feet, we continued to talk and read scenes. Again, with Ibsen this is completely appropriate. The psychological layering is so complex you have to go deep. With most shows you find out about the psychology as you go, working on it as you working on the physical aspect of the play, but this is different: Ibsen’s genius lies in his insight into the complexities and paradoxes of human behaviour, particularly when its comes to sexuality and relationships. How we behave and how we think we behave, as well as how we behave in contrast to how we think we should behave, is explored by Ibsen in a way almost no-one else has before or since. The characters’ sense of themselves is often very different to how they actually are, or how others’ see them. If anyone knew how we construct our personas, or have them constructed for us, it was Ibsen. Like Freud and Jung he recognised how we hid our true selves from ourselves and others, to such an extent that we can verge on mental illness. Its not for nothing that Danny Solomon, playing Torvald having played John (Jean) in Miss Julie, commented that this play felt far more vulnerable than Strindberg’s masterpiece.

Big themes that emerged today were lies and deception, both to ourselves and others, and the masks we wear in society, not just in public but in private. Nora appears to behave differently depending upon who she is talking to, and consciously wears a mask when she is with Torvald, even though she loves him. She even reveals to Christine, quite unconsciously, that her relationship with him involves dancing and acting for him. We see this in action in the first and last scenes they have together in the first Act, but at this stage Nora is not so critical of it as she becomes. Its what she thinks is normal, and we find its how she gets what she wants from Torvald. Indeed its how she came to save Torvald’s life, by coming up with a huge deception in order to bypass his stubbornness and pride and get him to go to Italy to recuperate from the illness he had. We realised just how vast this deception was, and although Nora did it for love, and although he is proud of it, the way in which this lie has grown between them is the fault line that is their undoing, because its the fault line Krogstad exploits. We remarked to Hannah that a wonderful thing to explore was how maintaining that mask became more difficult as the play goes on.

We worked hard on making that first scene between Torvald and Nora look like a positive one. Ibsen slowly reveals the abusive, controlling, unequal nature of their relationship as the play goes on, but in the first scene we should be under the impression it is basically a happy marriage. We noted how Torvald uses the word ‘we’ throughout, rather than ‘I’ as he does in the climactic scene at the end where he loses his temper. They appear to be united at the outset, but the play slowly reveals the rift between them and the lies their marriage is based on. We began to chart that process.

We did a lot of digging into back stories, how hard Nora has worked to pay off the debt and how depressed it has made her, even though she makes light of it. We also looked at how Torvald became sick because of how hard he worked to support the family, which revealed that he too has suffered. We also looked at the narcissistic way in which he thinks of himself as morally superior – even though the morality he expresses is not necessarily wrong – and mused on why everyone is aware that he needs to be kept from ugliness, death & decay. This need is what makes him so controlling of Nora, who is very aware of his boundaries. We asked ourselves what the trauma was that led to this deep insecurity that he’s not aware of, and that informs how he treats Nora.

We looked at Christine, Rank and Krogstad, and mused on their back stories. Back stories are vital in Ibsen because they tell you so much about motivation. Writing a biography of each character is something that really arose from actors performing Ibsen for the first time. He required a new way of approaching acting.

Having focussed on Torvald and Nora during the second day, today we delved deep into the psychology and life of Christine. Here is actress Heather Carroll talking about her:

Tell us a little about your work as an actor so far:

I graduated from ALRA, drama school, a decade ago and have worked with various companies and around the country since. I’m an Associate Artist of Oldham Coliseum and also Actors for Human Rights. I have worked in site specific work and immersive shows to main houses. My work has varied from Shakespeare to adverts – should you see an advert of a girl eating chicken nuggets with a ginger cat yes that is me. The one thing I love about being an actor is no day is ever the same, just like no project is ever the same – even if like me you have performed in shows when they have been remounted.

Is this the first time you have worked with Elysium?:

I worked with Elysium on an R&D of Between Two Worlds and recorded recently one of the COVID 19 Monologues, but this will be my first full production.

What character are you playing?:

I am playing Christine Linde

How do you see the character? What are your initial impressions from reading the script?:

I see Christine as a realist – she’s very pragmatic, she likes to have purpose – whether that be work/or being a mother to someone. I think she’s quite caring but also passionate about people doing the right thing.

How do you prepare for a role before rehearsals begin? What preparation have you done for Christine?:

I like to read the script a few times and right down my impressions of what I say about myself/other characters/things I need to look into whether that be words or reference points. For a show like Dolls House, I also have done some historical research to get the context of where someone like Christine would stand socially, but also in terms of her rights as a woman at the time as this seems so key to what drives her through the show. It also seems to create division between Christine and Nora although they are from the same place – their lives seem to have been very different. One creative thing I like to do is create a playlist for my character – sometimes this is what that person would listen to, but Dolls House I have created one that makes me think of Christine, her feelings and energy as much as I’d love to listen to 1870s songs, I’m not sure there would be too many choices on Spotify.

What do you think are the main challenges with your character as an actor?

For a character like Christine, I think major challenges are not to let contemporary Heather’s opinions and movements slip in. This means I sometimes have to leave my 2022 opinions on women’s rights, or the gender inequality in A Dolls House at the door because Christine is a person of her era. For movement it means focusing on how Christine’s life would have shaped the way she moves – she is a woman who has worked a lot of different jobs such as in a school, an office – she probably wasn’t doing yoga daily or sitting with her legs crossed on chairs!

Is this the first time you have worked on an Ibsen?

Yes, it is.

What do you think are the main challenges of working on an Ibsen? How is he different/ the same to other playwrights?

I think the main challenge with an Ibsen is remembering in his day he was almost a father of realism/naturalism and not getting lost in a world which may seem other to you as a performer. He’s different from his contemporaries because of his realism and the way he put a spotlight on social injustices and women’s rights – although he argued he was no feminist himself. I’m really looking forward to embodying Christine and giving her a voice.

What do you hope the audience will take away from the production?

I hope people will take away Ibsen’s illumination of women’s rights then and reflect on where we stand currently – yes, we have moved forward a lot – I can buy my own property, borrow money, vote – but gender equality isn’t quite there yet and if we look at marginalised groups of women we see even further gender inequality here in the UK – let alone globally where there are countries where women still can’t borrow money or own property in their name etc.

——————————————————————————————————

A DOLL’S HOUSE – Q&A WITH DANNY SOLOMON – PLAYING TORVALD 6.9.2022

Day two of rehearsals has been as intense and exciting as Day One. The day was given over to round table discussions about the characters, the world of the play, the style of acting needed and some of the challenges the text presented. We spent the morning focussing on Nora and Torvald who, in a sense form the core of the play, then in the afternoon we worked through Nora’s relationship with Christine, Krogstad’s relationship with both of them and then Dr Rank. In so doing we were able to really delve deep into who everyone was. Its incredibly important in rehearsals that everyone feels they can talk freely, can share ideas, discuss, debate, suggest and even argue without fear of being silenced or shut down. As the gender politics of the play are so sensitive and complex, everyone has strong feelings about it, so conversation was lively, but always with a common goal. We are company trying to pull together to realise Ibsen’s text, and we all share a humanist perspective, whatever our gender. We all have our own experience of the issues in the play, and we all want that represented; at the same time, we don’t want to impose our experience on the play in a way which distorts its own vision. This is a delicate balancing act, as its very easy to do, especially as director. In the end, all we have is the text, and we must try and extract everything we can about the characters based on what they say and do. The advantage of having a healthy debate with a multitude of perspectives in the room is that we increase the possibility of not imposing the wrong interpretation on the text. We challenge each other, but in a healthy way, and, we hope, will own the choices we make communally as a consequence.

What has struck us all is the subtlety with which Ibsen creates his characters and the milieu they operate in. There was a lot of discussion about how rounded everyone was, how each character had their good and bad qualities, how all of them were flawed, but how that didn’t detract from the central thrust of the play: Nora’s own journey to self-realisation and liberation. There is a huge temptation to see the play in terms of goodies and baddies, saints and sinners, but that isn’t how Ibsen operates. Everyone is multifaceted in the play, as they are in real life.

Key topics that came up during today included the whole issue of motherhood & the differing perspectives women can have on that; we looked at how that experience now differs from 1879 when the play was written. Even more important were the nature of marriage and the difference between it and a relationship in terms of commitment and how it involves navigating the instabilities, insecurities and conflicts of two people’s evolving psyches in a way that is harder to walk away from. We looked at how divorce had become easier since 1879 and what that meant in terms of how society and the position of women has changed, as well as the experience of children. We touched on what we felt about Nora’s abandonment of her children might mean, what motivated it and what we felt about it. We also delved deeply into the nature of an abusive relationship, how it can be unconscious as well as conscious, and how its can take time to wake up to that – something key to Nora’s journey. The willingness of the cast to discuss these highly sensitive and triggering issues made all of this very productive.

We also explored the underlying influence of Christianity in the play; even though Ibsen was brought up a Lutheran he rejected it in his young adulthood and became a free thinker, but nonetheless ideas of crime and punishment, guilt, forgiveness, redemption and, most of all, the possibility that someone can change are all central ideas underpinning the play. Can Krogstad be forgiven? Can Torvald be forgiven and can he change as he says he does? What is the meaning of the use of the word ‘miracle’ and then ‘miracle of miracles’ by Nora? Obviously she doesn’t mean it literally, but there is significance in the language, how it escalates from ‘a miracle is going to happen’ – her belief that Torvald will stand by her as she stood by him – to ‘the miracle of miracles would have to happen’ – she and Torvald would have to change so much that their life together would become a marriage – how she talks about no longer believing in miracles, and yet Torvald insists that he wants to. The possibility of change underpins everything Ibsen wrote and, in a truly tragical sense, those of his characters who can’t change, even if they want to, are destroyed, whereas those who can, like Nora and, to a lesser extend Krogstad, are ‘saved’. The network of imagery and ideas here is fascinating, and very influenced by the Christianity Ibsen also rejected.

The biggest task in the show is the actress playing Nora’s. Our Nora, Hannah Ellis Ryan, is throwing herself into the material with incredible intelligence, sensitivity and, most of all, generosity and grace. A more selfish actress would make the whole play about herself, but not Hannah. For her its very much an ensemble. Michael Meyer, the translator, always used to say that actors who want to granstand, who aren’t willing to play relationships with their fellow actors on stage, always fail with Ibsen, because what fascinated him was the complexity of relationships. Hannah understands this innately, and is engaging in depth with Nora’s connection with all the characters. Its exciting to watch.

The most challenging character to play after Nora is Torvald. We have noticed that of all the characters he is the one who we know least about. Everyone else has backstories; we know about the past of Christine, Krogstad, Rank, even the Nurse who brought Nora up, but we know next to nothing about Torvald’s back story or what makes him tick. Equally, how does one make a character who represents the worst of masculinity in so many ways in any way sympathetic? And yet for the play Tro work, we have to understand why Nora has been with him for so long, why she has risked everything to save him once, and spends the entire play trying to protect him from the truth, while simultaneously being convinced that if the truth comes out Torvald will stand by her?

Here is our actor, Danny Solomon, on his approach to the part. As his comments show, Danny is a core member of Elysium and has played the leads in all but one of its productions so far. Here are his thoughts:

Tell us a little about your work as an actor so far:

After Graduating from acting school in 2011, I have worked mainly in theatre in London, Manchester and the North East.

Some of my highlights have been Danny and the Deep Blue Sea which played at the Hope Mill Theatre in Manchester; A powerful play about two broken people who find salvation in each other. And also, The Man Who by Peter Brook which played at the Tristan Bates theatre in London in which I played different characters who are living with various neurological conditions.

Is this the first time you have worked with Elysium?:

No. I co-founded the company with Jake Murray a few years a go and have been quite heavily involved ever since. One of my favourites was actually our first play we put on; Owen McCafferty’s Days of Wine and Roses – a play about a couple from Belfast trying to create a life in London whilst battling with alcoholism.

It was also a blessing to play Johnnie in our production of Athol Fugard’s Hello & Goodbye – a play about two siblings confronting the harsh reality of their past and present.

What character are you playing?:

Torvald Helmer.

How do you see the character? What are your initial impressions from reading the script?:

I see Torvald as a proud man who is proud of what he has achieved in his career.

He is a religious, law abiding man who takes pride in providing for his family and has a strong moral code which he expects those around him to live by.

How do you prepare for a role before rehearsals begin? What preparation have you done for Torvald?:

I start by reading the play a good few times. I like to be very familiar with the lines my characters speaks before I go in to rehearsals so I will divide the play up in to units depending on when characters enter or exit, thoughts changing etc. To learn lines, I will record myself speaking the other characters and leave gaps for me to speak. I then repeatedly go through these units speaking as my character so I’m able to get the words ‘in to my body’, in a way. These characters’ words and phrasings are not mine so I like to be able to help them feel less alien when I start walking and talking as them.

I will also find out what the character says about themselves and what others say about them. This gives me a good idea of both how the character sees themselves and how others see them. So, this may give me clues as to how the character holds themself physically, how they speak etc.

I also really want to discover what is important to the character and what would they do to get/hold on to that thing.

What do you think are the main challenges with your character as an actor?

I think the main challenge is building the relationship between Torvald and Nora so that we are able to see how their marriage has lasted this long.

From the beginning of the play, Torvald talks to Nora in ways that are condescending, patronising and bullying at times. Mostly though, I don’t feel he is aware he is doing this. He firmly believes his way of conducting himself in their relationship is the way of love and care for his wife. And alongside the jibes are acts of love and admiration. They are a very tactile, physically expressive couple who love a good hug and play games with one another. They also seemingly have a healthy sex life!

So, bringing out the light amidst the darkness.

Is this the first time you have worked on an Ibsen?

Yes, this Is my first Ibsen play professionally.

What do you think are the main challenges of working on an Ibsen? How is he different/ the same to other playwrights?

Ibsen writes hugely complex characters who are each struggling with their own fears and doubts and pasts.

I feel the challenge will be adjusting to the context of the time the play was written (1879) and what certain decisions and actions will mean for the people in this world, what is it at stake and what these people stand to lose in this world can be quite different to how we live today.

When I re-read A Doll’s House, and especially the last act of the play, I was stuck by how powerfully progressive and modern it seems.

Rather than differences, I could see its similarities and direct influence on works by great dramatic playwrights like Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, Eugene O’Neill, John Osborne, Caryl Churchill and Lorraine Hansberry.

What do you hope the audience will take away from the production?

I’m hoping for it to spark debate and conversation. It deals with complex issues concerning gender equality (or lack thereof), class, money, marriage, blackmail, abuse, mortality, abandonment, suffering and love. So, there is a lot to go on!

Ultimately though (and hopefully without spoilers), the nature of the ending of the play is one of hope. It reminds us that it is right to study and question the world and one’s own circumstance within it.

A DOLL’S HOUSE – Q&A WITH HANNAH ELLIS RYAN – PLAYING NORA 5.9.2022

Rehearsals for A Doll’s House started today. We began with a meet and greet, in which the cast and creative team introduce themselves, look at the set, discuss some logistics and so on, followed by a read through of the play and a discussion afterwards. This discussion sees everyone air their feelings about their characters, the themes of the play and share ideas. We’ll go into detail more as we work through the play, but one thing that was incredibly clear was just how powerful it still was. Absolutely everyone in the room had had their own lived experience of the action of the play, whether in relationships or marriage, so everyone had impassioned and deeply felt things to say. Because Ibsen goes to the heart of the experience men and women have of each other, both joyful and painful, everyone found themselves in the play and wanted to say something important. I can’t think of a piece of work that had that affect on people so powerfully. Its a mark of a great play that everyone who encounters it becomes instantly engaged with it, and that it is able to spark passionate debate even now, 150 years or so on from when it was written.

More tomorrow, but we begin our rehearsal week with an interview with each of the actors as they embark on this play. First up is Hannah Ellis Ryan, co-founder of Elysium. Hannah is a writer and a producer as well as a first rate actress. This is her third part for the company after playing the Woman in Jez Butterworth’s The River and Hester in Hello And Goodbye.

Nora is one of the theatre’s greatest parts for a woman’s. It requires great range. Here are Hannah’s thoughts on it and Ibsen in general:

Tell us a little about your work as an actor so far:

I moved to the UK from Australia ten years ago and have been really lucky to work on a huge range of projects in that time. One of my favourites was working in London on Kill Climate Deniers at The Pleasance Theatre; a hilarious comedy with a core message about climate change. I also had the honour of being part of ITV’s Coronation Street in a very juicy storyline as part of the McDonald family, playing villain Hannah Gilmore. It was an incredible experience and I made friends for life.

Is this the first time you have worked with Elysium?:

I have performed in two Elysium’s shows prior to this, both of which were a huge privilege. I played ’The Woman’ in Jez Butterworth’s The River and Hester Smit in Hello & Goodbye last year. I have to say that Hello & Goodbye was an absolute treat – the sort of role actors dream of. Gritty, fulfilling, complex. As it was the pandemic, we worked really closely together, in a rehearsal room with essentially just our director (Jake) and fellow actor (Danny). It was a very special way to work and I think helped create the intimate, vulnerable and raw emotion that show needed.

What character are you playing?:

Nora

How do you see the character? What are your initial impressions from reading the script?:

I see Nora as resourceful and intelligent. Because she is also full of joy, she can come across as flighty or simple, but she has a wealth of intellectual resources at her disposal and proves this in the play. She does relish the little things in life, as well as supreme gratitude for the love of her family and how lucky she is, compared to others. She wants to suck the marrow out of life and enjoy every second. Until she can’t.

How do you prepare for a role before rehearsals begin? What preparation have you done for Nora?:

I start of by reading the play over and over again without judgement. I try to just read and let it wash over me, take in little things and just enjoy the experience of the play as an observer. Then, once I have done this a number of times, I do script analysis work of writing out everything that’s said about Nora, what she says about others and what she says about herself. From there, I build myself a timeline of events, both in the play and before. In rehearsals I’ll play around with some physical work and different approaches to pace and language. Nora talks A LOT, so it’ll be fun to play around with her rhythms and how she tells a story, in a way that is captivating and joyful.

For a play like this it’s also important to do research on the period and understand the implications of money, status and family in this time. The stakes are everything in A Dolls House – what is at stake for Nora.

What do you think are the main challenges with your character as an actor?

The biggest challenge in playing Nora is her swift thought changes and rapid pace. She carries a lot of scenes and feels responsible for carrying the audience through important emotional shifts and changes. Her emotional journey and what is at stake for her is the heartbeat and backbone of the play, so ensuring this is both clear, while powering the story forward, feels like a challenge (one I will relish!)

Is this the first time you have worked on an Ibsen?

I worked on Ibsen in drama school, but this will be my first time professionally.

What do you think are the main challenges of working on an Ibsen? How is he different/ the same to other playwrights?

I think the main challenge will be the beautiful and complex language. This is a play that relies on communicating these words as if they flow effortlessly out. It takes a lot of work to make something seem effortless – so I feel that will be the core challenge.

What do you hope the audience will take away from the production?

I hope people get to experience the magic of iconic theatre. Elysium’s work is so high calibre, and with A Dolls House as the text, my primary hope really is that people just enjoy the magic of live theatre and feel that spark. It still feels like we are recovering from our years of the pandemic and being deprived of larger scale / larger cast work. So I hope that those we reach in the North East enjoy watching an iconic play, and the plays relevance still speaks for itself.

————————————————————————————————-

A DOLL’S HOUSE – A TRIBUTE TO MICHAEL MEYER by Jake Murray (AD) 27.8.2022

There is another reason to do this version too: the translator, Michael Meyer. There have been many other translations of Ibsen’s plays, but none have yet surpassed his, although many have claimed they have. Before him, Ibsen was a niche playwright in the English-speaking world, admired by other writers, artists and members of the intelligentsia, but lately unknown by the general population. By the time he died in 2000, Meyer’s translations had made both Ibsen and his younger contemporary, Strindberg, powerful presences in the English-speaking theatre, performed all over the world on stage and screen by the greatest actors of their generation, Laurence Olivier, Vanessa Redgrave, Leo McKern, Maggie Smith, Miranda Richardson, Albert Finney and so many more. The debt we owe him is immense.

What was it that made Meyer’s translations so successful and so important? Before WW2, the only English versions anyone had access to were those by William Archer. Archer, who was attached to the Royal Court in London at the time when it included the likes of George Bernard Shaw, John Galsworthy and Harley Granville-Barker, was an Ibsen evangelist, and worked hard to bring him to the English speaking world. Without his efforts, the UK would not have encountered Ibsen, nor would Shaw, Galsworthy or Granville-Barker, or others such as Wilde or Pinero written the works they did. All were were hugely inspired by him, and wrote similar plays written in naturalistic prose which tackled the social and moral questions of their day. If we owe a debt to Meyer, we owe one to Archer too. But Archer didn’t have a gift for language, so his versions remained remained stiff and stilted, laden with Victorian turns of phrase and lacking in flexibility. Considering the rich textual layers of Ibsen’s work, and their moments of real poetry, this gave his work the quality of a glacier; people could see what great plays these were, but their full greatness seemed locked under ice. In addition, he didn’t always understand the plays fully. Ibsen brought a complex psychology to his characters that often left even the most insightful critics baffled. There were reasons why other explorers of the ambiguities of human motivation such as Freud and Strindberg responded to him most powerfully. Archer sometimes shared that bafflement of those who understood him less, so crucial dimensions to the work were lost.

Meyer changed all that. His work brought Ibsen’s words up fresh. His own love of theatre, and his own felicity with language transformed Ibsen’s powerful Norwegian into fluid, compelling, exciting English stage dialogue. Most significantly, Meyer was fluent in Norwegian, which meant that his translations were derived from a direct understanding of the original. This may seem an obvious thing, but in fact most stage adaptations since WW2 have not been done by people who know the original, especially now. By far the more common practise involves theatres employing someone who is fluent in the original language to do a literal ‘crib’ version, which a playwright then turns into stage dialogue. This explains why, even with superb adaptors like Ted Hughes and Tom Stoppard, they appear to be able to master a multitude of tongues. Ted Hughes, for instance, did brilliant versions of plays by Wedekind, Lorca, Aeschylus, Euripides, Racine and Seneca, but to be able to do this he would have had to be fluent in German, Spanish French, Latin and ancient Greek, which seems unlikely. What makes his versions so good is his own ability to wield language powerfully as a major poet in his own right, but his obvious admiration of the originals. Hughes recognised the genius of the great writers of the past and the intelligence and emotional depth of what they wrote, so knew that his job as a translator involved living up to that. Not for him glib, superficial translations, or clever ‘improvements’ which ‘updated’ the great works of those who came before us. For Stoppard it was the same. As a consequence both men’s stage adaptations stand out, but neither always knew the original versions.

With Meyer you get the same approach, the same belief that the translator’s job is to serve the vision of a great artist, and convey it the public as authentically and compellingly as possible, but with the added dimension that he knew the original intimately thanks to his awareness of the language. Michael learnt Norwegian and Swedish while teaching in Scandinavia after the War. He fell in love with both countries and cultures. This first hand knowledge of the language and the background meant that his translations spring right from the source in a way adaptors working from someone else’ literal rendering do not. It wasn’t easy for him to begin with. When he was first approached to translate an Ibsen – Little Eyolf, one of his most complex and multi-layered works – Meyer’s Norwegian was weaker than his Swedish; when he returned to it years later to rework it he was horrified by the errors he made. But by the end of his career he had translated masterful versions of all of Ibsen’s major plays, from Brand to When We Dead Awaken, and the same for Strindberg. This required him to master experiments in form and language from both. Ibsen’s break through plays, Brand and Peer Gynt were epic verse dramas rather than naturalistic prose works like A Doll’s House, and as he developed as a playwright he evolved his naturalism to include symbolism and, towards the end, began to edge back to poetic language again. Strindberg was even more avant garde and experimental ranging from the radical naturalism of Miss Julie to the out-and-out dreamlike surrealism of A Dream Play and The Ghost Sonata.

Meyer mastered all of this, but everywhere strove to keep himself out of the translations. As he put it in his memoir Not Prince Hamlet:

“The most difficult thing, if the translator is a creative writer himself, is to keep himself out of it, to resist leaving his thumbprint. Gogol once observed that the ideal translation should be like a window pane. One should not be aware that it exists.”

He was scrupulous in avoiding anachronisms and made it a rule that he would never use a word that was not current at the time the play was written. What he understood most was the challenge of conveying the subtext, the subtle nuances of language that Ibsen brought to the stage for the first time and required a new approach from actors, directors and translators. Unlike Shakespeare’s characters, who are direct in what they say, either to each other, to themselves or to the audience via soliloquies, Ibsen’s characters are inhibited by feelings of guilt, or responsibility and, most powerfully, the sexual morality of their day. Although driven by the same passions we are driven now, too often they find themselves thwarted in what they feel they can say, sometimes through shame, sometimes through fear, sometimes through vulnerability. 19th Century European society was one which favoured self-sacrifice and disapproved of open sexuality. Ibsen’s characters want to break free of both, and the drama of his best plays derives from that struggle and their inability to do so. This reflects itself in the way they express themselves, censoring their real feelings through shame about what they really want. How does one render these inhibitions in stage language, and how does one convey enough that actors know what their characters are really saying so that they can convey that to audiences? Meyer again:

“One of the most difficult problems that face a play translator is rendering the sub-text: the meaning behind the meaning, what lies between the lines. Ibsen was a supreme master of sub-text. If I ask you a question concerning which you have no inhibitions, such as the weather or football or your feelings about a film or a dress, you reply directly. But if I question you on a subject about which you feel guilt or inhibition – your relationship with your sexual partner, or with your parents, or religion or whatever it may be – then you reply not directly but evasively and in a circumlocutory manner. Almost all of Ibsen’s characters are, like Ibsen himself, deeply inhibited people, and at the crises in his plays they are brought to bay with what they fear and have been running away from. Then they talk evasively, saying one thing but meaning another; but to an intelligent reader, director or actor, the meaning behind the meaning is clear, and the translator must word his sentences in such a way that he sub-text is equally apparent in English… This combination of evasiveness and clarity is, I think, the most difficult of all the problems that face an interpreter of his plays.”

Again, no-one has met this challenge as well as Meyer did. One of my favourite examples appears in his version of Ghosts, the play he wrote after A Doll’s House. Central to this work is the complex relationship between the two lead characters, Mrs Alving and Pastor Manders. Most productions focus on Mrs Alving and her young, Hamlet-like son, Oswald, relegating Manders by playing him as a caricature of a Priest, reactionary in his views and the butt of Ibsen’s biting satire and social criticism. But again, Ibsen is so much more profound and subtle than that. The central tragedy of the play is the thwarted love between the two of them, which has blighted both their lives and that of Mrs Alving’s son. As the play unfolds we gradually learn that as young men and women Mrs Alving fell in love with Manders and left her dissolute, abusive husband to be with him. But, tragically, the young and charismatic Manders, loyal to his Christian ideals and aware of his position as a Pastor, sent her back. The agony of her rejection and the pain of her marriage from then on have cast a blight on her life ever since.

At a key moment in the play she tries to confront Manders about what happened. Meyer renders it brilliantly:

MANDERS: Aha – so there we have the fruits of your reading. Fine fruits indeed! Oh, these loathsome, rebellious, free- thinking books!

MRS ALVING: You are wrong, my dear Pastor. It was you yourself who first spurred me to think; and I thank and bless you for it.

MANDERS: I?

MRS ALVING Yes, when you forced me into what you called duty; when you praised as right and proper what my whole spirit rebelled against as something abominable. It was then that I began to examine the seams of your learning. I only wanted to pick at a single knot; but when I had worked it loose, the whole fabric fell apart. And then I saw that it was machine-sewn.

MANDERS (quiet, shaken) Is this the reward of my life’s hardest struggle?

MRS ALVING Call it rather your life’s most pitiful defeat.

MANDERS It was my life’s greatest victory, Helen. The victory over myself.

MRS ALVING It was a crime against us both.

MANDERS That I besought you, saying: ‘Woman, go home to your lawful husband,’ when you came to me distraught and cried: ‘I am here! Take me!’ Was that a crime?

MRS ALVING Yes, I think so.

MANDERS We two do not understand each other.

MRS ALVING No; not any longer.

MANDERS Never – never even in my most secret moments have I thought of you except as another man’s wedded wife.

MRS ALVING Oh? I wonder.

MANDERS Helen –

MRS ALVING One forgets so easily what one was like.

MANDERS I do not. I am the same as I always was.

MRS ALVING (changes the subject) Well, well, well – let’s not talk any more about the past. Now you’re up to your ears in commissions and committees; and I sit here fighting with ghosts, both in me and around me.

Look at how subtly and sensitively Meyer translates this. If Manders never had feelings for her, why does he refer to telling her to go back to her husband as ‘my life’s hardest struggle… my life’s greatest victory… the victory over myself’? One doesn’t struggle unless there is something to struggle with, one doesn’t win a victory over oneself unless something in oneself needs defeating; its obvious that Manders was as attracted to Mrs Alving as she was to him, and the denial of his own desires was a battle he had to fight.

He goes on to say ‘Never even in my most secret moments have I thought of you except as another man’s wedded wife’. Again, this can’t be true, as it would contradict what he has just said about his victory over himself. Equally, he didn’t need to bring this up, rather his own conscience has done so. Notice how after Mrs Alving questions this he calls her ‘Helen – ‘, not ‘Mrs Alving’. He’s come to visit her in the play in his professional capacity as a Pastor, but ‘Helen’ is an intimate term of address. One wonders what might have said had she not cut him off with ‘One forgets so easily what one was like’. That he knows there were sexual feelings between them is made obvious by his choice of words ”I am here! Take me!’

Underlying the whole sequence is the unspoken desire from Mrs Alving for him to finally say ‘Yes, I was in love with you, yes I wanted you.’ In performance this should be a key scene; this is the scene in which, if Manders met Mrs Alving’s honesty with his own, their lives could go in a different direction. But Manders lies to himself and her, and in doing so kills the last chance they might have in their old age of being together.

There is so much to work with here, so much that is unstated, so much that is hidden, so much beauty and pain, and yet so many productions miss it completely. Unless there is suppressed chemistry between Manders and Mrs Alving the tragedy does not work. When I took a group of students to see a production of Ghosts in London, one of them turned to me in the interval and said ‘Did she and he have a thing when they were younger?’ I replied ‘If you have to ask me that then the production hasn’t done its job.’ The truth was that neither the translator nor the director had understood this about Ibsen’s text. Meyer had, and as a consequence his rendering of this passage was more sensitive and subtle than anything that production could have even imagined. It perfectly exemplifies the depth of insight and and attention to detail that informs his translations.

There are two other reasons why Meyer’s versions of Ibsen continue to have this power. As well as his work translating the plays, he was the leading expert on Ibsen’s life in the English-speaking world. His three volume biography of the playwright was ground-breaking in its day and remains definitive. Its a masterpiece of biographical writing by any standard, and is written as compellingly as a novel. Meyer writes about Norway, Europe and the cultural and political context of Ibsen’s plays as if he was there, and creates a portrait of the writer as if he knew him personally. Again, all this knowledge informs his translations. Meyer didn’t approach the texts from a superficial position, nor did he impose a Presentist interpretation on the action or dialogue; rather he created his translations from a position of profound and detailed knowledge of the man, his world and his vision. Such knowledge adds layers to his translations that more modern, ‘accessible’ versions don’t.

Lastly, another strength of Meyer’s translations was his ability to collaborate and learn from his co-creators. In all his published scripts Meyer always pays tribute to two men, Michael Elliott and Casper Wrede, for their insights into the texts. Both men were great directors; Elliott made his name with landmark productions of Ibsen such as Brand with Patrick MacGoohan, Peer Gynt with Leo McKern and The Lady From The Sea with Vanessa Redgrave, Wrede, a Finn who had come to England to direct, was equally successful with productions of Strindberg’s The Father and Creditors. It was Elliott’s grasp of stagecraft and Wrede’s knowledge of Ibsen’s language and themes that added extra dimensions to Meyer’s translations that give them yet another, powerful edge. Meyer paid tribute to Wrede rigorous support in particular:

“I owe a triple debt to Wrede. He taught me about playwriting and the theatre in general, he taught me the difference between translating plays and novels, and he turned me from a dilettante into a professional… Casper knew Norwegian as well as he knew Swedish, Finnish and English… He sat with Ibsen’s original text on his knee while I read out my version. Line by line he destroyed what I had written. ‘You’ve used twelve words where Ibsen used seven.’ ‘Yes, but – ‘ ‘You’re translating it as though it was dialogue in a novel. Play dialogue is much tighter.’ ‘You’ve put the key word in the wrong place… The line should be evasive, you’ve translated it too densely… You’ve put in an image that wasn’t there, Ibsen’s sparseness is better… This line would get a laugh in Norwegian, yours won’t… Ibsen repeats a word that appeared three lines earlier, you’ve missed that.” By the time we had finished, barely a line of my original version remained.”